As fitness professionals, we are taught that corrective exercise improves movement safety leading to fewer client injuries. Have you ever stopped to ask yourself if this represents the whole truth?

The truth is corrective exercise often falls short of clients’ goals. Now let’s dive into 3 big reasons why, and how to bridge the gap.

Myth #1: Corrective exercise fixes movement

Corrective exercise typically focuses on one joint or muscle at a time. For example, calf stretching increases ankle dorsiflexion. Bridges activate the gluteus maximus. We spend time on the corrective exercises, yet we don’t see a difference in the client’s movement in the workout that follows. Their bodies rebound to their previous movement habits.

Why do clients continue to demonstrate previous movement habits, even after doing corrective exercise? Complex movement is dependent on neuromuscular control (how well the nervous system coordinates the movement). Neuromuscular control depends on how the brain organizes input from the nerve endings in joints, ligaments, tendons, muscles, fascia and skin, to create movement output.

This means that you must first recognize that a client’s form is speed and load dependent, and then coach clients for nervous system integration. For example, a back squat, front squat and overhead squat all have different technique. The technique changes based on the load. Because of this, the alignment cues, muscle activation cues and timing cues are all completely different for each situation. Being sensitive to load and speed variations will help you hone in on which cues to provide for the basic kinetic chain check points (ankle, knee, hip, shoulder and head alignment).

After embracing form variations, we need to find cues that lead to clients exhibiting changed performance. Cueing options include:

- Verbal: What you say to the client.

- Tactile: How you use your hands or external objects like bands, balls or rollers to promote proper alignment or muscle activation.

- Visual: Feedback that the client takes in through his/her eyes, such as looking in the mirror, or watching a video of his/her movement.

- Environmental: How you set the physical space for movement success. Environmental setup is one of the most often overlooked, yet most valuable cueing methods. It allows clients to problem solve and create real movement learning, and many “aha” moments along the way. Environmental cueing is like motivational interviewing to help a client’s abilities naturally emerge; instead of telling the client what to do, you set up an environment that facilitates solutions.

Myth #2: Corrective exercise prevents injury

Corrective exercise is designed to increase range of motion, muscle and connective tissue length, muscle activation and muscle strength. When these factors are not optimized for the workouts that follow, the deficits present injury risk factors.

Injury, however, is multi-factorial. An injury prevention focus requires you, the coach, to address each factor. These factors fall into two categories: intrinsic (factors within the client’s body) and extrinsic (factors outside the client’s body). Here is a quick checklist you can use to audit your injury prevention coaching plan:

Intrinsic risk factor minimization:

Client’s health status: Before working with a client, start with a health history and physical activity readiness questionnaire. If clients have risk factors or medical conditions, see if you can have permission to correspond with the client’s medical provider directly. Questions to ask the provider include:

- “What would you like me to avoid?”

- “What can I do to help this client attain better health?”

- “Are there any special precautions we need to observe before, during, or after workouts?”

Once you have the information, follow it instead of trying to come up with creative workarounds.

Client’s energy: While providing meal plans is out of scope for most fitness professionals, professionals can still inquire about nutrition, hydration and nutrient timing relative to workouts. It is within a fitness professional’s scope to modify or postpone workouts if the client has a relative lack of caloric intake or hydration to perform safely.

Client’s fatigue and focus: Fatigue continues to be the leading factor contributing to injuries. Fatigue alters neuromuscular control, which decreases clients’ abilities to operate within safe movement zones. Focus also takes a lead in injury prevention, as distracted clients cannot attend to key sensory information that their brain needs to coordinate safe movement output. Asking clients about sleep, stress and recent illness can help detect these movement detractors. If, as a coach, you notice trends like 4 hours of sleep per night, caffeine-reliance or chronic stress elevation, engaging in lifestyle coaching (or referring out for larger scale challenges) take a paramount seat in your professional relationship. It is also your responsibility to modify the workout intensity and complexity to meet the client’s physiological capabilities, without exceeding them, in each session.

Extrinsic factor minimization:

Environment: Do you conduct safety walkthroughs before your sessions? If you are indoors, check the flooring, ceiling, air temperature, electrical wires, noise levels and equipment. If you are outdoors, check the air quality, temperature, humidity, ground consistency and surrounding structures. Many fitness professionals overlook these steps, leading to clients falling, equipment malfunctioning or environmental incidents like bee stings.

Clothing and footwear: New clients may not be familiar with what to wear. Experienced clients may be coming directly from work. Clients that observe specific clothing cultural practices may need to modify movement. Some environments change temperature several times each day, leading to a client having difficulty warming up or cooling down. Providing clients individual education on what to wear for your intended environment and activity sets them up for success.

Proximity to objects or people: Collisions happen. In the fitness environment, most of them are preventable. At a minimum, there should be at least a 3-4-foot perimeter around each client’s activity to avoid collision with objects or others.

Myth #3: Corrective exercise enhances the value you provide clients

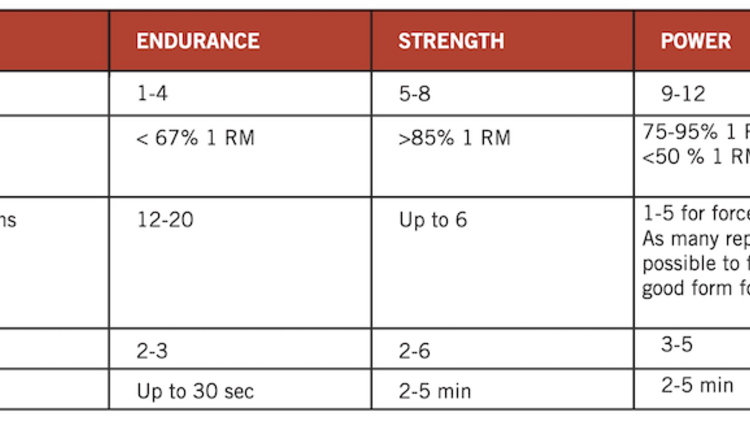

Many publications suggest 4 weeks of corrective exercise re-setting time between each 12-week progressive endurance, strength and power training block. This lengthens every program section from 12 weeks to 16 weeks. While this is simple physiology-based math, clients focus on goals and emotions, not exercise physiology.

Here’s where many fitness professionals create a client motivation gap. For most clients, extensively educating them on physiology detracts from perceived value. Clients want to see their results. Results commonly have outward measurements like scale weight, body composition change, lifting PRs, or endurance sport PRs. That achievement is intrinsically driven by deep super-whys and motivation sustainability.

When fitness professionals introduce language like “corrective exercise,” it creates a connotation that the client is doing something wrong. Very few people enjoy being told they are doing things incorrectly, and this inference can both decrease motivation and increase disparity in the client’s perceived value of efficient goal achievement.

To avoid the pitfall of explaining the need for corrective exercise, fitness professionals can use strategies (like motivational interviewing) to uncover how clients feel about movement, and which elements they want to see performed differently. Once fitness professionals start diving into uncovering clients’ senses of movement ease and efficiency, the door for movement coaching unlocks a whole new world of daily movement PRs that help clients recognize their wins.

Next steps

As you move forward in your fitness coaching career, take a moment to use these concepts to audit your practices. If you’d like to modify your own approach, use the same strategy you would with clients: commit to one small change, make it a habit, then after a few weeks of consistency, add another small change.