The following is an excerpt from: "Can You Outrun a Donut?: The The Surprising Impact of Nutrition and Exercise on Your Weight, Health, Mortality, and Performance" by Jason R. Karp, PhD, MBA

"Julie, what if I told you that you could still enjoy a peppermint espresso mocha latté, or even a Coca-Cola or Snickers bar, if you run or bike before or after?”

Julie’s eyes grew. “What? No way!”

Believe it or not, aerobic exercise, even a single workout, prevents the decline in blood vessel endothelial function caused by overconsuming sugar.

To learn more, let’s go to Iowa City, Iowa, one of the most literary cities in the world, where scientists at the University of Iowa had subjects drink three sugar-sweetened beverages per day for seven days. Each drink contained a whopping 75 grams of glucose in ten fluid ounces. That’s 300 calories in each drink, for a total of 900 calories of sugar per day and 6,300 calories of sugar for the week-long experiment.

Half the subjects also cycled on a stationary bike for forty-five minutes per day, five of the seven days, at a moderate-intensity (60% to 65% max heart rate). After seven days, flow-mediated dilation (the amount an artery dilates in response to increased blood flow, which is commonly used to assess blood vessel endothelial function), both in absolute magnitude and relative percentage, was significantly reduced in the non-exercise group (that’s bad!) and significantly increased in the exercise group (that’s good!).

This finding led the scientists to conclude, “Regular moderate-intensity aerobic exercise mitigates the deleterious effects of repeated sugar-sweetened beverage consumption on endothelium-dependent vasodilation.” Exercise is such a powerful stimulus that your arteries are protected from the sugar even if you exercise the day before consuming a high-sugar snack.

Julie wiggled forward in her seat, as though about to object, but I continued.

“Wait, it gets better. Want to know what happens when you exercise the day before eating pizza?”

To find out, we need to take a trip to Trondheim, Norway, on the Norwegian Sea, and visit the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Norway is not exactly known for its pizza, but nevertheless, scientists there had healthy men consume a vegetarian mozzarella pizza as a high-fat meal—911 calories, with 48.3 grams of fat, 80.4 grams of carbohydrates, and 38.5 grams of protein—the day after doing two different types of workouts on a treadmill, separated by a week, each of which burned the same number of calories:

1. Moderate intensity (walking 47 minutes at 60% to 70% max heart rate)2. High intensity (four reps of four minutes each at 85% to 95% max heart rate with three minutes recovery between reps at 50% to 60% max heart rate)

Each study participant did both workouts plus a third “control” condition of no exercise the day before eating the high-fat pizza, with the workouts and no-exercise condition all done in random order. Endothelial function was assessed by flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery in the arm, using vascular ultrasound.

Both the moderate-intensity and high-intensity exercise improved flow-mediated dilation, whereas it was unaltered in the control trial. All participants had the greatest flow-mediated dilation after the high-intensity exercise. The moderate-intensity exercise did not completely protect vascular function from the food-induced reduction in flow-mediated dilation; however, the post-meal decrease in flow-mediated dilation was significantly less than that observed in the control trial.

By contrast, the high-intensity exercise not only completely protected the blood vessel from the reduced flow-mediated dilation caused by the high-fat pizza, but actually resulted in greater vascular function than initially assessed at the start of the study, before any of the workouts or eating the pizza. Examining the effect of the pre-pizza-eating workouts on antioxidant status, the scientists found that antioxidant status was reduced in the no-exercise condition, maintained with moderate-intensity exercise, and elevated with high-intensity exercise, revealing a strong relationship between exercise intensity and blood vessel protection from oxidative stress.

In other words, aerobic exercise—and, to a greater extent, high-intensity aerobic exercise—completely eliminated blood vessel damage caused by eating a high-fat pizza.

“Shut the front door!” Julie exclaimed. “That’s amazing!”

If we leave Trondheim and travel 5,000 miles across the North Atlantic to the desert in Tempe, Arizona, we find a similar study nine years later. Scientists at Arizona State University compared the effects of two different interval workouts on endothelial dysfunction caused by eating a high-calorie, fast-food meal. Participants did both workouts in random order:

1. 4 reps of four minutes each at 85% to 95% max heart rate with three minutes active recovery between reps2. 16 reps of one minute each at 85% to 95% max heart rate with a one-minute active recovery between reps

A third no-exercise condition served as the control.

As in the study in Norway, participants consumed a high-fat meal, this time a McDonald’s Big Breakfast with hotcakes, a buttery biscuit, eggs, hash browns, and hot sausage patty, with a side of milk. The total nutritional composition of the meal put the Norwegian pizza study to shame: 1,250 calories, containing 63 grams of fat (including 22 grams of saturated fat), 128 grams of carbohydrates, and 44 grams of protein.

But even all that fat clogging the arteries wasn’t a match for exercise, as both high-intensity interval workouts equally improved the endothelial dysfunction caused by the McDonald’s Big Breakfast and significantly increased flow-mediated dilation compared to the no-exercise condition.

If we leave Tempe, Arizona, and travel to Montreal, Québec, we find another team of researchers who subjected fifteen healthy, young men to McDonald’s meals for breakfast, lunch, and dinner for fourteen consecutive days, amounting to an average of 3,441 calories per day and a daily average of 150 grams of fat (41 grams of saturated fat), 422 grams of carbohydrates, and 100 grams of protein. In addition to eating three McDonald’s meals per day, participants did a high-intensity interval workout every day on a treadmill for the same fourteen consecutive days, consisting of fifteen 60-second sprints at about 90% max heart rate with a 60-second walking recovery between sprints.

After fourteen days, there was no change in the participants’ body weight, BMI, and waist circumference. Body fat percentage decreased. Fasting blood glucose, lipoprotein(a), and C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation) all significantly improved. No changes were found for all the other measured cardiometabolic parameters, such as blood pressure, liver enzymes, apolipoprotein B, and insulin resistance.

Humans are not the only animals for whom exercise benefits their blood-vessel health. Even mice do!

From Montreal, we travel to Boulder, Colorado, where scientists at the University of Colorado observed mice over the course of their lives consuming a standard diet of low-fat chow or a high-fat/high-sugar Western diet in the absence or presence of aerobic exercise.

Aging impaired endothelium-dependent vessel dilation, which was accelerated by the Western diet. In mice consuming normal chow, aortic wall stiffness increased with age and worsened at any age with the Western diet.

Interestingly, lifelong aerobic exercise completely prevented age- and Western-diet-related vascular dysfunction across the lifespan, with the protection appearing to be a result of mitigation of oxidative stress and inflammation. Granted, we’re talking about mice, and mice have a much shorter lifespan than humans, but still, these observations in a mammal with similar biology to humans are remarkable.

Julie placed her tired head in her cupped hands. “That’s a lot of traveling and research studies. I don’t even know what time it is anymore!”

“Ah, it’s easy to lose track of time when reading an interesting book,” I said, smiling. “And there’s a lot to unravel and discover. That’s why we take these trips and also critically review everything. Each study is like a puzzle piece, Julie. Each human study and animal study. All pieces.

“While they’re interesting by themselves, they mean little by themselves. We can’t see the whole picture by looking at the pieces apart from the picture, or the picture apart from the pieces. When we see the pieces isolated from the picture, there is no picture, only pieces.

“To fully understand how each piece fits into the picture, even transforms it, we have to see each piece as a piece of the whole picture, not isolated from the whole, by itself. And when we piece together all the individual pieces, the entire picture begins to take shape. Begins, because the picture is never completely finished, Julie. It is only the picture we have now, comprised of the pieces we have now. And the more pieces we have, the more we can predict what the future picture will look like. The more we can see. And then, there it is, right in front of us.

“Exercise is so powerful, it shields your blood vessels from stressors, such as a diet high in sugar and saturated fat. And people all over the world study it.

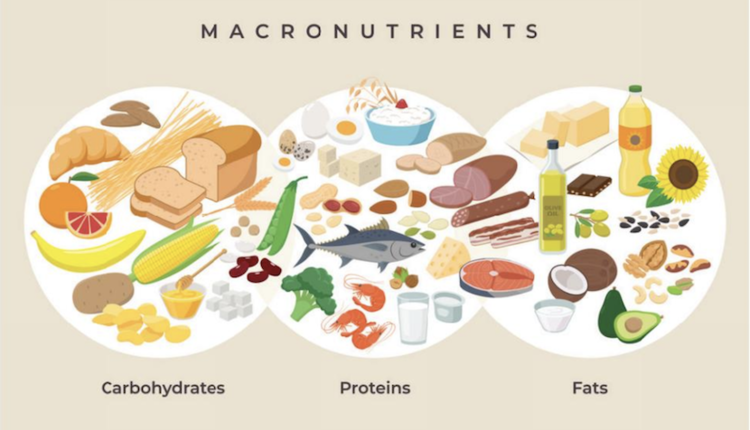

“You know, the incendiaries in the media like to say that sugar is poison and people should avoid it like the plague. What an irony it is, then, that sugar is your body’s preferred and immediate source of energy, with glucose metabolism via anaerobic glycolysis evolving long before fat and its associated aerobic metabolism came along.

“What I’m saying here is sugar is not inherently bad, Julie. It’s actually your workout buddy. Sugar only harms your blood vessels if it just sits there for a while. And you have control over whether or not it just sits there for a while.”

Dr. Jason Karp is a run coach, sport and exercise scientist, and author of 16 books and more than 400 articles. He is an IDEA National Personal Trainer of the Year award winner and two-time recipient of the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition Community Leadership award. He has been a college professor of exercise science, has lived and coached runners in Kenya, and is currently the editor of Track Coach magazine. His run coaching certification was obtained by fitness professionals and coaches in 26 countries before being acquired by International Sports Sciences Association. His TED Talk, How Running Like an Animal Makes Us Human has inspired people around the world. He outruns donuts every day in San Diego, California. Follow him @drjasonkarp on Instagram and find his books on Amazon.